智福 (Ze Fook) Fu Dog of Good Fortune

智福 (Ze Fook)

stoneware, glaze, gold

11 × 10 x 16 inches (L x W x H)

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

智善 (Ze Seen) Fu Dog of Compassion

智善 (Ze Seen)

11 × 11 x 15 inches (L x W x H)

stoneware, glaze, gold

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

Chrysocolla Crystalline Silkworm

2025

20 × 9 × 15 inches

stoneware, crystalline glaze by Ahn Lee

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

Jade Crystalline Silkworm

2025

19 × 15 × 9 inches

stoneware, crystalline glaze by Ahn Lee

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

白虎 White Tiger

白虎 White Tiger

2024

27 x 17 x 17.5

Ceramic, glaze, mother of pearl luster

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

GOAT (FOURTH PILLAR OF DESTINY)

一路好走

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

GOAT 一 FOURTH PILLAR OF DESTINY

一路好走

2024

22 x 10 x 21

Ceramic, crystalline glaze

The Goat is the Fourth and Final Pillar of Ahn’s Chart. The Goat is Blue and Light Yellow/White and of Yin Water just as the First Pillar of Ahn’s Chart. The Fourth Pillar represents the years of being an Elder. The Goat is a weaver, a storyteller, a nurturer and a stronghold in the community.

UNTITLED, TIGER (THIRD PILLAR OF DESTINY)

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

TIGER (THIRD PILLAR)

2024

27 x 17 x 17.5

Ceramic, glaze, mother of pearl luster

The Tiger is the Third Pillar of Ahn’s BaZi. Meaning, the time of adulthood, 30+ up until the time of being an elder. This is a Green Yang Metal Tiger. This Tiger is the Ultimate Predator of the chart. The Tiger has learned/is learning how to respond to adversity, to go after what it wants and succeed. The Tiger holds an element of healing/medicine and mysticism. This Tiger’s Mother Pillar is intuition/emotion and ancestral Karma. This Tiger chases the Abstract and the Light.

RABBIT (SECOND PILLAR OF DESTINY)

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

RABBIT (SECOND PILLAR)

2024

9 x 7 x 13

Ceramic, crystalline glaze, gold luster

The Rabbit is the second pillar of Ahn’s BaZi. Meaning, the Rabbit is the time of adolescence through early adulthood (around 30 years old). The Rabbit is the Ultimate Prey of the chart, yet also the survivor. Ahn’s Rabbit represents the healing of relationships, of the self, and of prioritization of relationships. This is a Yin Wood Rabbit of the color Green.

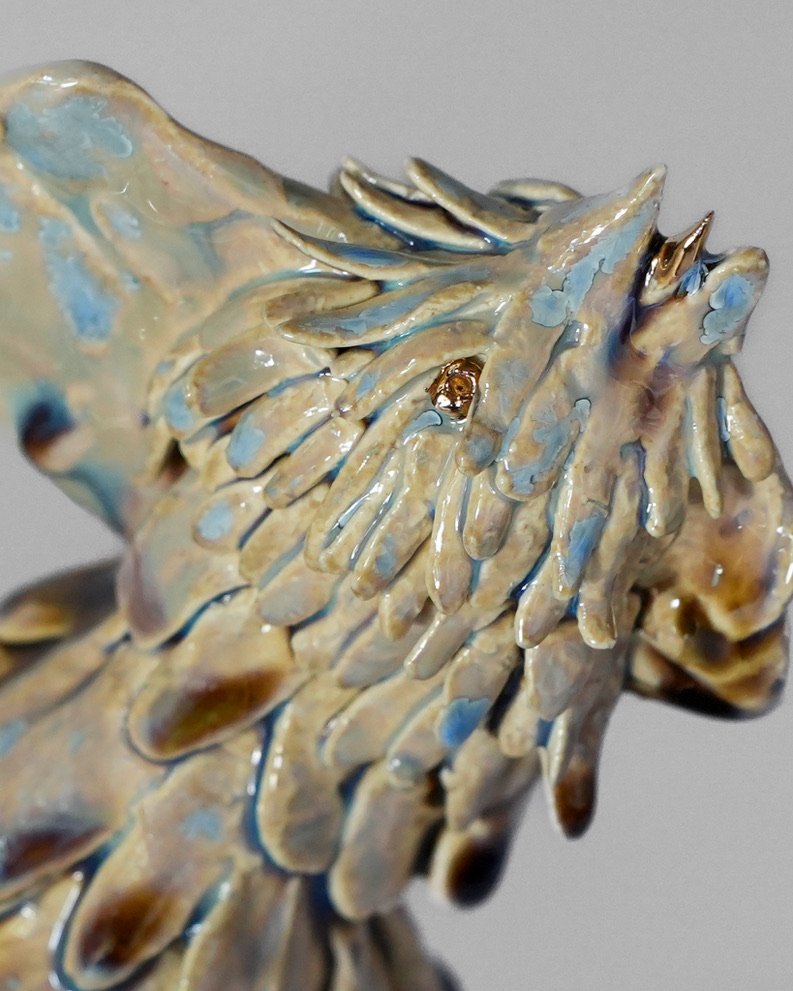

ROOSTER (FIRST PILLAR OF DESTINY)

Hadley Raysor Photography www.hadleyraysor.com

ROOSTER (FIRST PILLAR)

2024

8 x 16 x 18

Ceramic, crystalline glaze, gold luster

The First Pillar of Ahn’s BaZi, the Rooster is a Yin Water Rooster. The Rooster is the year in which Ahn was born, until adolescence. This rooster is fierce, and is of the colors Blue and White.

夢想未來 (Dream Future)

Photo by Aidan Jung

These I will not lose

Photo by Aidan Jung

Under the Same Sun with Edge on the Square

September 30th, 2023

Chinatown’s 2nd Annual Contemporary Arts Festival

Photos by Edge on the Square, Joyce Xi and Henrik Kam.

凤凰我爱你, To See and Be Seen, To Love and Be Loved

凤凰我爱你, To See and Be Seen, To Love and Be Loved

2023

18 in x 19 in x 27 in h

Ceramic, glaze

Photo by Aidan Jung

The Phoenix is perhaps one of the most known and auspicious of Chinese mythological beings. Its rare appearance is foretelling of harmony and played a key role in the creation of the cosmos. The Phoenix also represents immortality and both masculine and feminine qualities, transcending gender binaries and moving through time, space and lifetimes. My Phoenix has my partner’s top surgery scars, and has intentional detailed cracks where I removed and replaced the chest as a ritual part of creating this piece.

慢慢, slow

慢慢, slow

2023

20 in x 20 in x 13 in h

Ceramic, glaze

In ancient Chinese mythology, the tortoise with the snake wrapped over its shell is one of four symbolic creatures each pointing in a different direction. As a starting point for creating my queer take on Chinese mythology, I began with the snake and turtle, the north. While I significantly altered the symbolic creatures of each of the other directions, I chose to keep this one the same - a turtle and a snake signifying the element of water; and of stability, happiness and longevity. I added a bottle of testosterone in the mouth of the turtle, and carved on its back “我爱你。你是我的宝贝。” (I love you. You are my treasure.)

合家平安 May our family be safe and peaceful.

合家平安 May our family be safe and peaceful.

21 in x 20 in x 20 in h

Ceramic, glaze

Photo courtesy of Edge on the Square, 2023

In Chinese mythology, the toad symbolizes fertility, immortality, wealth, and connection to other worlds. The toad is often correlated with creation myths. A toad with coins is a common feung shui symbol, known for drawing wealth into a space. On the chest of the lower toad is a symbol for longevity, carved into the chest as armor. A smaller toad sits on top of the bottom toad, and the two share a tongue, referencing queerness and the mating position of frogs. On the coins in this piece, I carved 合家平安, a four character Chinese saying and one that includes the character for my name, 安. I used the character 合 rather than 阖 because the latter references someone else family, while the former references one’s own family. Together, the characters wish one’s own family safety from harm and peace. Typically this is placed near or above one’s entryway. I have one in my home that hangs on my doorknob, gifted to me on the lunar new year by my mother.

蚕王 (silkworm deity)

蚕王 (silkworm deity)

2023

28” L x 7” W x 30” H

Ceramic, glaze

A celestial silkworm deity, part of a new series of queered Chinese folk deities.

Photo by Aidan Jung